How “Race-Minimizers” Quietly Erase Black Soldiers from World War II

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Thomas Reinhardt: How History Is Silenced

- Andrea Orzoff: “Holocaust-Minimizers” and Nazi Reenacting

- From Holocaust-Minimizers to Race-Minimizers

- Race Minimalization In Practice

- Race-Minimizing and the “Good War” Story

- Why This Matters for Dutch and American Audiences

- Asking Better Questions and Neutrality

Introduction

When you read an English-language book about World War II, you expect to read about all aspects of the war: nations, units, different soldiers from around the globe. But often, one group is almost invisible: Black American soldiers. That's not just a mistake. It tells us something about how we remember history.

During the same war, the United States maintained a segregated military and treated Black people as second-class citizens. In June 1945, the Army totaled 8.266.373 men, of which 694.818 (9.33%) were Black, which is similar to their percentage of 10% of the U.S. population at that time.1 Black Americans fought for what was called a “Double V”: victory over fascism abroad and victory over segregation at home. How that contradiction is remembered, or quietly minimized, matters. To understand this process, it helps to start with two historians who study how uncomfortable histories are pushed aside: Thomas Reinhardt and Andrea Orzoff.

Thomas Reinhardt: How History Is Silenced

In his article “200 Years of Forgetting: Hushing up the Haitian Revolution,” Thomas Reinhardt examines why the Haitian Revolution is often unmentioned in histories of the modern world. Between 1791 and 1804, enslaved people in Saint-Domingue overthrew French colonial rule, freed themselves from slavery, and established Haiti as the first Black republic. It was one of the most important revolutions of the time. Yet many books either ignore it or treat it as a minor side story. Reinhardt argues that this is not a coincidence. He identifies two main strategies for silencing inconvenient history.

Total omission

The first strategy is brutally simple: you do not mention the event at all. Reinhardt writes that authors “just shut the hell up” about the Haitian Revolution.2 If people never see it on the page, they will not know it happened. The event drops out of the events that define world history.

Decontextualization and drowning it in background noise

The second is more subtle. An event can be mentioned, but buried under other details or pulled out of its proper context. This can be done by zooming in on a single detail, so that it loses its significance in history or the Haitian Revolution is pulled out of its proper context, such as when it is only viewed from a Western economic perspective. In that frame, it becomes a “failed” revolution instead of a successful slave uprising that terrified slaveholding societies across the Americas. Reinhardt explains that the choices about what is included, what is left out, and how things are framed matter. All of these shape how we remember history.

Andrea Orzoff: “Holocaust-Minimizers” and Nazi Reenacting

Andrea Orzoff brings a similar perspective to a very different topic: Nazi reenacting and fascination for the Waffen-SS. In an article in The Atlantic titled “What's Wrong with Nazi Reenacting,” she discusses the case of Rich Iott, a U.S. congressional candidate who spent years reenacting as a soldier in the 5th SS Panzer Division Wiking. Many reenactors insist they are just interested in uniforms, tactics, and military history. They claim they are not Nazis and have nothing against Jews or racial minorities. But Orzoff looks at the websites and materials they use. On sites devoted to SS units like Wiking, she notes that there are detailed accounts of campaigns, orders of battle, and equipment, but there is a lack of information about the Holocaust, about war crimes, or about the SS role in carrying out genocidal orders or exterminating people. To describe this pattern, Orzoff uses the term Holocaust-minimizers.

Holocaust-minimizers

Holocaust minimizers do not usually deny the Holocaust or claim the SS did nothing wrong during World War II. But they show little interest in its victims and focus instead on what they admire about the SS: “courage,” “elite” status, or military effectiveness. Orzoff argues that this places them on the same continuum as outright Holocaust deniers. They are at a “milder” end of the spectrum, but they share a goal: rehabilitating aspects of Nazism by disconnecting the soldiers from the genocidal framework within which they operated. Once the Holocaust is treated as optional background, and the SS is remembered mainly as a tough fighting force, a deeply distorted image of the past emerges.

From Holocaust-Minimizers to Race-Minimizers

Both Reinhardt and Orzoff show how powerful actors shape historical memory by silence, by framing, and by selective interest. Those same mechanisms appear in the way many books and films remember Black American soldiers in World War II. In work on Black participation in the war, a parallel category emerges: the race-minimizer.

Race-minimizers

Race-minimizers know that Black Americans served in World War II and often know that the U.S. armed forces were segregated by law and policy, but treat those facts as marginal, awkward, or irrelevant to the main story they want to tell. Within that perspective, segregation, the Double V campaign, experiences of Black Americans, become footnotes or disappear altogether. Race-minimizing does not deny that Black Americans existed, but it decides to treat race as unimportant, to leave it out because it complicates the story they want to tell. Where Holocaust-minimizers focus on “interesting” military aspects and treat genocide as background, race-minimizers focus on weapons, units, and a “good war” narrative while treating segregation and Black service as background or optional.

Race Minimalization In Practice

To see how race minimalization works in practice, it helps to look at two concrete examples: uniform reference books by Andrew Mollo.

Case Study 1: A World War II Without Black Americans

In the book World Army Uniforms Since 1939 written by Andrew Mollo and Digby Smith, there are 349 uniformed figures and 14 depict American soldiers during World War II.3 Not one of these soldiers is a Black American, even though statistically it would have been appropriate to have one of these figures be a Black American. The book does contain an Indian soldier (figure 64), a colonial Italian soldier (figure 70), a British West African soldier (figure 197) and a woman in the Soviet army (figure 175).

No mention that the U.S. Army was segregated, or that Black soldiers served in seperate units. Viewed through Reinhardt's lens, this is a textbook case of silencing by omission: if you “just shut the hell up” about Black troops, they drop out of the visual memory of the war. There isn't even race-minimizing here, because Black Americans aren't featured at all. It's interested in uniforms and weapons, but not in how race and segregation shaped that same army.

The result is a U.S. military that appears raceless and/or inclusive. A reader can leaf through the U.S. plates and never see a Black American. The visual memory of “what World War II looked like” becomes a line of white American soldiers, sailors, and airmen. This might give the impression that World War II was fought by white American troops and various colonial forces, but not by Black Americans in U.S. uniform. That impression is wrong.

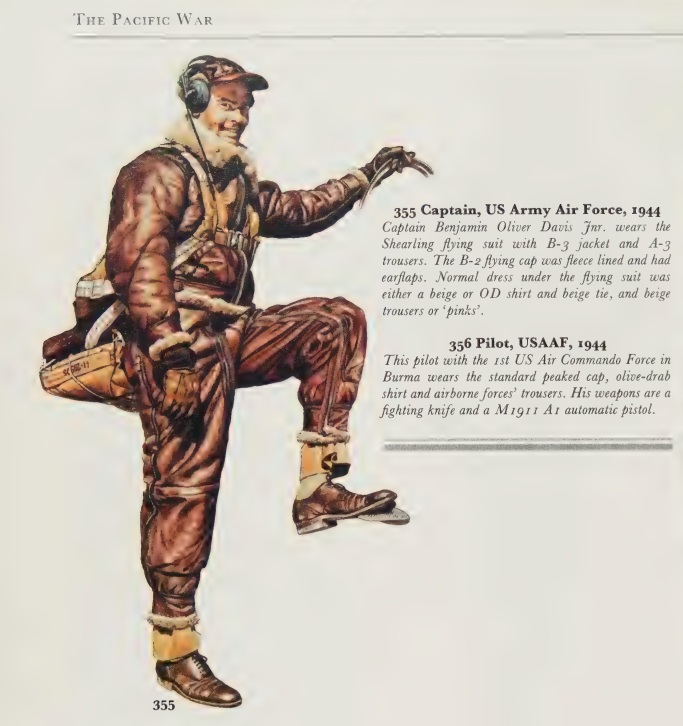

Case Study 2: Benjamin O. Davis Jr. in the Wrong Theater

Andrew Mollo's The Armed Forces of World War II: Uniforms, Insignia and Organisation is a richly illustrated reference book4. It contains 365 drawings of soldiers from many different nations, each in uniform. Out of those figures, 41 depict members of the American armed forces: soldiers, sailors, and airmen. The book also includes colonial troops serving in European armies and even shows a Samoan fighting alongside American forces.

In that book Mollo does include an illustration of Benjamin O. Davis Jr., the first Black general in the U.S. Air Force and commander of the 332nd Fighter Group, also known as the Tuskegee Airmen. He had a distinguished career in the US military. Including him could have been a good way to show that Black soldiers were part of the history of World War II, because there is no mention elsewhere in the book that the U.S. Army was segregated, or that Black soldiers served in seperate units, such as the 92nd Infantry Division or the 761st Tank Battalion.

However, the problem is that in this book Davis appears in the section on the Pacific Theater of War and the focus is on his uniform, not on the him or his service. The 332nd Fighter Group didn't operate in the Pacific Theater. This disconnects him from the context in which he served. It turns him into a generic American pilot rather than an example of how Black pilots overcame racial barriers. Race is not discussed at all.

In Reinhardt's terms, this is the second kind of silencing: the figure is present, but taken out of context. The zoom is so specific, in this particular case on his uniform, that he as a figure has lost its significance. People can point to Davis in the book and say, “They included a Black officer,” but the way he is presented in does not do justice to what he experienced or represents. Instead of teaching readers about the Tuskegee Airmen's role in the European war and in the struggle against segregation, the image becomes an isolated token.

Race-Minimizing and the “Good War” Story

On their own, these choices might look like simple oversights. However, when people examine many books, they show a broader pattern in how World War II is remembered in popular media and reference works. Racial segregation and discrimination inside the U.S. military are pushed out of view. For Black Americans, the history was never that simple. Many enlisted or were drafted while still denied equal rights at home. They served in segregated units, were often confined to labor and service roles, and had to fight for chances to prove themselves in combat.

The Double V campaign, victory over fascism abroad and over Jim Crow at home, captures the reality that for Black soldiers the war was fought on two fronts. Race-minimizing accounts do not completely erase these facts. Instead, they push them out of sight, treating them as background or specialist knowledge. The central narrative of World War II remains white and relatively uncomplicated.

Why This Matters for Dutch and American Audiences

For Dutch audiences, World War II is often remembered through the lens of occupation, resistance, collaboration, and liberation. American troops appear as liberators who brought an end to Nazi rule. That narrative is true, but incomplete. Among those liberators were Black American soldiers who served in segregated units, encountered discrimination from their own side even as they faced German fire and returned home to a country that still denied them equal rights.

For American audiences, race-minimizing allows a comforting image of the “Greatest Generation” while sidestepping the uncomfortable reality that many of those who fought for democracy abroad were denied democracy at home.

For anyone interested in Black history, the issue is clear: when books and films minimize race in World War II, they minimize the specific achievements and struggles of Black soldiers, sailors, airmen, and marines. Their courage lay not only in facing the enemy, but in doing so within a system that treated them as less than equal.

Asking Better Questions and Neutrality

Race-minimizers do not always have bad intentions. An author might simply think that uniforms and organizations are “neutral” topics. A filmmaker might focus on one particular story and not consider how casting and framing affect who appears at the center of the war. The end result is still the same, that Black soldiers aren't represented. Erasing Black soldiers entirely, as happened at Margraten Cemetery doesn't honor them either.

Race-minimizing is not about accusing people. It is about recognizing that even well-regarded books and films can quietly sidestep the realities of racism and segregation. If World War II is going to remain a central story in our shared historical imagination, whether in the Netherlands, the United States, or elsewhere, it should be presented in a way that includes the full range of those who fought, and the full complexity of what they were fighting for. That means not only adding Black soldiers to the picture, but also restoring the context that makes their service, and their struggles, visible again.

Footnotes

-

Ulysses Lee, The Employment of Negro Troops (Washington DC, 1966), 415. ↩

-

Thomas Reinhard, “200 Years of Forgetting: Hushing up the Haitian Revolution”, Journal of Black Studies, 35.4 (2005) 252. ↩

-

Andrew Mollo and Digby Smith, World Army Uniforms Since 1939 (Dorset, 1986). ↩

-

Andrew Mollo, The Armed Forces of World War II: Uniforms, Insignia and Organisation (London, 1987). ↩